The relation between reason and passion has been a fascinating subject to philosophers for centuries. Plato visualized reason and emotion as two horses pulling a chariot, with the charioteer struggling to make them work as a team. Modern society often pits “the head” and “the heart” against each other leading us to believe that the two are antagonistic to each other. The reality is a bit more complicated. Most people are of the belief that even basic emotions only cloud our judgement, thus affecting our ability to make rational decisions. Could it be true that emotions are simply a vestigial brain function in an environment that seeks and rewards efficient and precise decision making?

Darwin labelled emotion as an evolutionary tool capable of adaptation, like any other physical characteristic. For example, immediate danger signals fear, that allows us to avoid harmful situations. From the context of evolution, emotion creates a pressing need to react to evolutionary cues. You might suppose that we humans are controlled less by instinct compared to other animals. But in fact, we have a greater repertoire of instincts that allows us to make complex and sophisticated decisions several times a day without even needing for us to stop and think about them.

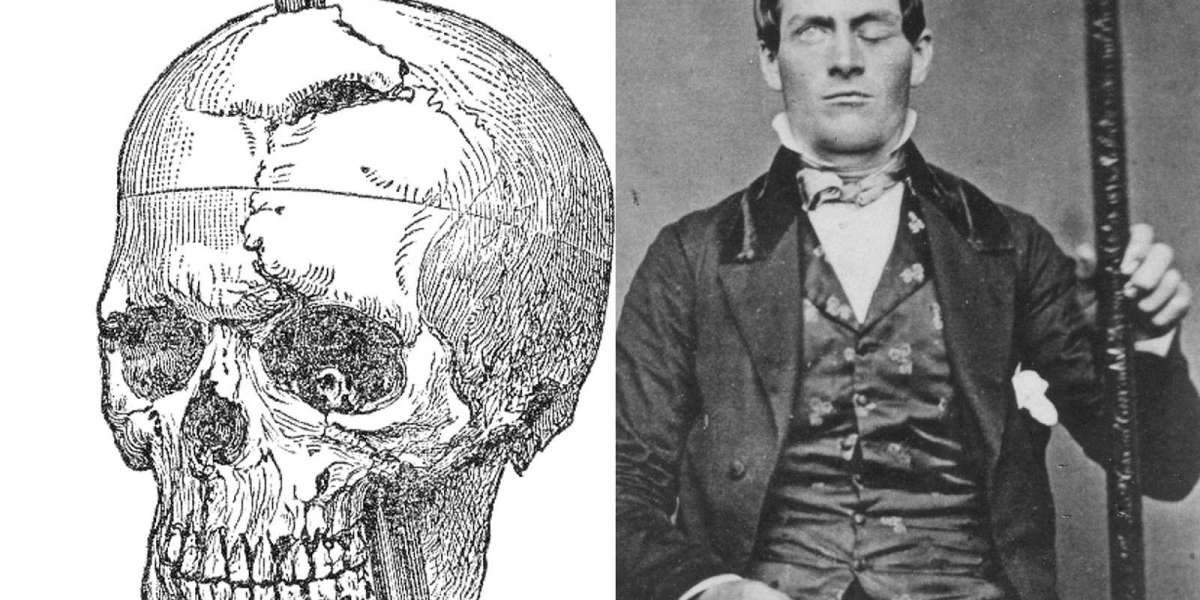

In a ground-breaking research, scientist Antonio Damasio studied patients that had brain damage in the frontal lobe, one of which was Phineas Gage. Gage, a railway worker, had a rod go through part of his frontal lobe.Miraculously, he recovered, however, he became moody and aggressive, incapable of making decisions or finishing tasks. He no longer remained a functioning member of society even though he regained most of his mental function. Another one of Damasio’s patients, Elliot, was a brilliant lawyer prior to his unfortunate accident. Post recovery, he retained his IQ, however, he spent his time poorly, got caught in details and lost all sense of priority. “I never saw a tinge of emotion in my many hours of conversation with him: no sadness, no impatience, no frustration,” Damasio wrote.

In more such patients, the conclusion that was derived was that with the loss of emotion, their lives fell apart because they couldn’t make the simplest decisions. Damasio theorised that in confusing decisions with conflicting alternatives, we decide what course to take my weighing the options. In other words, we reason. In the neurological pathways to reasoning, there exist “markers” i.e. chemical records from previous experiences which are stored in the prefrontal cortex of the brain.

Research has proved that the dichotomy of logic vs feelings, head vs heart is more a social construct than hard science. In fact, the two are so closely entwined in each other that the ordinary individual cannot discern the processes as they take place. Even with what we believe are logical decisions, the very point of choice is arguably always based on emotion. The way forward is to cultivate thought processes that involve healthy emotions as opposed to unhealthy ones such that it urges our brain to arrive at decisions that lead to us accomplishing our goals.